Where did Dad’s English come from and what was it like?

DISPONIBLE EN FRANCAIS VIA CE LIEN

This is the second of two portraits exploring some of the experiences which shaped the way Mum and Dad spoke English. As someone who had always been on the lookout for different varieties of English when I was growing up, I wondered if there was a connection between this childhood attraction to the oddities of the language and an adult life spent teaching my English mother tongue as a foreign language. This made me think about the way the language was spoken at home – after all, we know that the way parents speak and function in a language influences the way their children do the same.

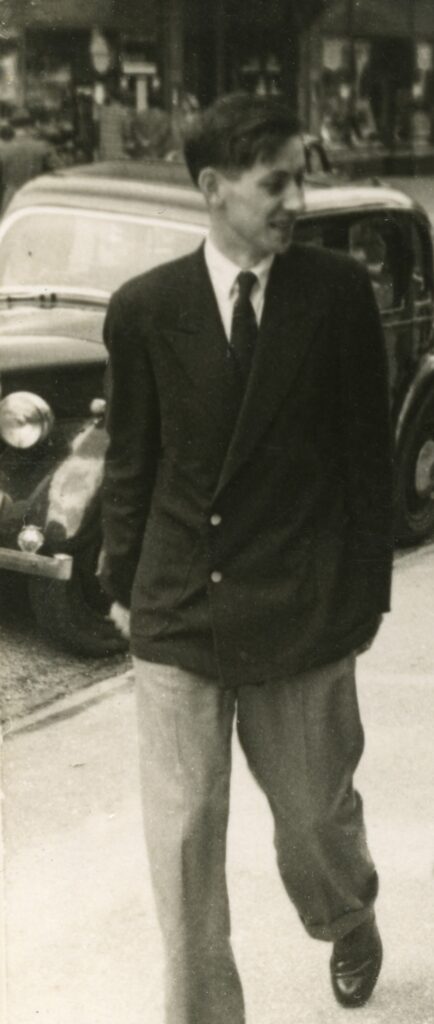

I began by writing the portrait of my mother’s English which you can read here. Dad’s is different again because he travelled a path which taught him to learn how to fit into whatever language environment he found himself in, both at home and abroad.

Family

Dad was born Kenneth Kenny in Dublin in 1932. His father, Desmond, was a Dubliner whose own father imported pianos, accumulating business debts which made family life uncertain. But young Desmond was a sociable, enterprising fellow who would meet his future bride when working as a journalist. Ken’s mother, Eva Farrell, originally from Booterstown, a coastal Dublin suburb, was running The Bohemian Picture Theatre when Desmond‘s paper sent him to interview her as the first woman to manage a cinema in the city. There’s no trace of the article, but they married in 1921 and moved south to Waterford where Desmond wrote for The Freeman’s Journal, until the newspaper’s premises burnt down during the Civil War in 1922 and it was time to go back to Dublin. Desmond ultimately became a Civil servant in the Department of Social Welfare, while Eva used her genius raising endless money for the Catholic Church. I wish I knew more about them but we only met once. What I do know for sure is that Eva gave birth to 9 children of whom only 5 would see adulthood.1

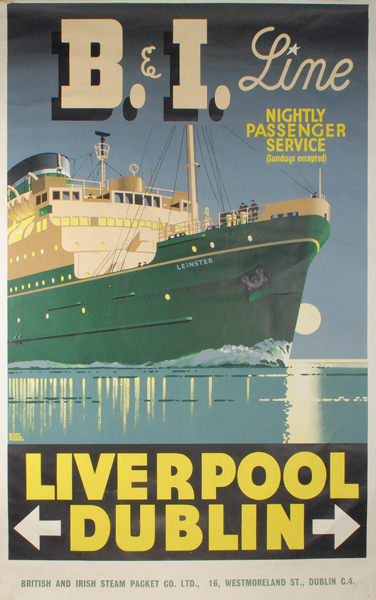

Promotional Poster – Source whytes.ie

Dad left home at 18 when he joined the Merchant Navy as a Radio Officer2 and practically never returned. Working with shipping companies out of Liverpool, he was constantly travelling to foreign places and Dublin wasn’t somewhere he wanted to go back to. He met Sheila, our mother, on the ferry on one of his few return trips to Dublin, but she was from Birkenhead – which would give him another reason to turn away from Ireland.

As a result, our only real childhood family connection with the Emerald Isle came years later when relatives would occasionally pass through our house for Sunday lunch. The person we saw most often was Aunty Marion, Grandma Eva‘s youngest sister, who had long since lived and worked in London. She was very forward-looking, a great listener, and there was a new flow to the conversation when she came – always bringing something sweet in her bottomless bags.

Other less frequent Sunday callers who sneaked Irishness through the hall door3 were Dad’s brothers and sisters who came in ones and twos. Having taken holy orders, his older siblings Mylo, Des4 and Nora hadn’t married, but his youngest sister Evelyn had a big family like ours5 and we also went to see them. The Kennys were all good, lively talkers in large gatherings, but you knew that the real conversation would only get going once we children had left the meal table. Who knows what they talked about then? I can only imagine.

Irish undertones

I can see now that there were always Irish undertones to the way Dad spoke English but, as a kid, I wasn’t especially aware of that. All I knew was that I was in England, we were born there and we were English. There was no looking back to Ireland. I remember him officially renouncing his Irish Citizenship to become British in 1965, but I never saw him as a foreigner before that. The common language to both nationalities being English, there was no issue there for me.

Perhaps after he officially became a Brit there was one time when I realised he was an ex-Irishman. That was the day he took my brother Simon and I to Twickenham to see England v Ireland in the 1972 Five Nations Rugby Championship.. All three of us rooted for England but Ireland won in injury time, much to the delight of a very English-sounding Irish supporter behind us who had shouted “Come on, Ireland!” all the way through. I remember Dad commenting : “Well, at least somebody’s happy.” Yes, we told ourselves, Dad was an England supporter now.

Sometimes his Irishness made us laugh when it popped back in the way he said specific words. Gas was always /gɑːs/ and never /gæs/. Butter was /ˈbʌtə/ for us, but more like /ˈbɒtəʳ/ for him. Pudding wasn’t /ˈpʊdɪŋ/ but something closer to /ˈpʌdɪŋ/.6 These pronunciation anomalies were things all his own, leftovers imported from some foreign place. But Dad’s English only turned completely green again when Irish family were there. The sign he had truly changed colour was when the expression “Ah, sure” (with the rhotic-r) became his standard way of responding to what was said.7

A language chameleon

Ken was a language chameleon who was able to don the cloak of what was being spoken around him. Originally this was woven from different cloths. There was English, but oddly Latin would have been familiar to him too. Not only because he grew up a Catholic in the age of the Latin mass, but also because his elder brothers who, as highly educated priests, were fluent Latin speakers able to talk about anything at all in the language which they would also use at home for wry remarks and private jokes which Dad liked to share. The Irish language would have been around too, even though he never mentioned it.

How did that change in later life? He developed a knack for tuning into people who spoke differently which helped him to blend into conversations. His years as a sales manager travelling abroad professionally and working with foreigners found him picking up their accents and expressions. This was particularly the case when doing business with Americans – unsurpisingly, given the multiple connections between Irish and American English – and there came a new dimension when he worked for an Italian company. Did he need to learn Italian for that? No, he would say, he could get by just fine with Latin and English. And he even managed to sound Italian when talking English to his Italian colleagues on the phone.

Although he couldn’t speak any foreign languages, he had a good ear and, as I observed once when he came to see us in France, was always able to follow what was going on around him. He could listen through the static thanks to his years as a Radio Officer, which had also given him fluency in Morse Code, another universal language, which he could also oralize as easily as he could send it electronically. That was certainly a fun thing when he did it.8

Learning father tongue

Much of what I share here is the result of putting together the pieces in a puzzle for which there was no convenient picture on the box to start with. It only really began when I settled in France where people saw me as Irish because my name is Kenny and asked me which part of Ireland I was from. They saw something I hadn’t, so it became something I had to address. Mum quickly told me all she knew on her side. Dad simply pointed me towards his cousin, Yvonne Robins, who filled in the family tree, and I took it from there and found the fullness of the Irish connection.

What about all those languages? English, Latin, Morse Code. Our Ken was an unusual mix, as we all are, and seems to have sidestepped the question of foreign languages by only learning universal languages. If this now seems obvious, it had previously never occurred to me. He couldn’t pass on the Irishness because he had moved on from there and was already in the world of English as a global language that we are all aware of today.

Maybe my ability to revel in the way people from different cultures and backgrounds use English as a first language or a foreign language comes from growing up with somebody who was always there watching as the language changed around him. A chameleon, always ready to change his spots.

Still want more?

You can read about the background to my mother’s English here. Obviously there are connections but each parent seems to have travelled their own path. And maybe reading this has triggered thoughts on the place of language in the family where you were born. If you would like to share, I would love to hear about it. And please share this article if you think it deserves it.

More Foreign Affairs coming soon.

- While most deaths were birth-related, the family’s first born, Gerald, died aged 11 from the after-effects of a bout of rheumatic fever 5 years earlier. You can read more about him here. ↩︎

- More details about how this happened can be found here. ↩︎

- Like all Brits we came in through the front door. For Dad, it was the hall door, the Irish name. ↩︎

- Mylo and Des were missionaries in Africa for many years and were also fluent in Igbo, the Nigerian language. ↩︎

- I am number 2 of 6. Angie came first, and after me came Simon, Louise, Lawrence and Dan. ↩︎

- This page from the Cambridge online dictionary helps decode words written in phonetic symbols. ↩︎

- According to the delightful irishslang.info website, “ah sure” is part of a family of expressions : “When sumtin controversial has just been said and deres no good n’ sayin nytin worth sayin, this is wha is said. Means absolutely feck all.” I hope that clears up the mystery. ↩︎

- You can find more Ken’s years working with Morse Code in a post called Dublin Lad Learns Morse. ↩︎

4 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback: