CLIQUEZ ICI POUR UNE VERSION FRANCAISE DE CET ARTICLE

Nebraska – a character-building recording

Welcome to the continuing Songsmith series in which I give space to individual songs which keep coming up on my inner jukebox. Writing about them changes the way I see them, puts them in perspective, and actually makes room for other tunes on that most private of all playlists.

Today’s post is different. It’s not about one song. It’s about a mood created by a whole album recorded in unusual conditions, focusing on private worlds made public ; an album so untypical of the artist who made it at the time that the record company accepted to release it with little or no publicity. Since then, it has remained largely overshadowed by the artist’s flashier, more spectacular public successes.

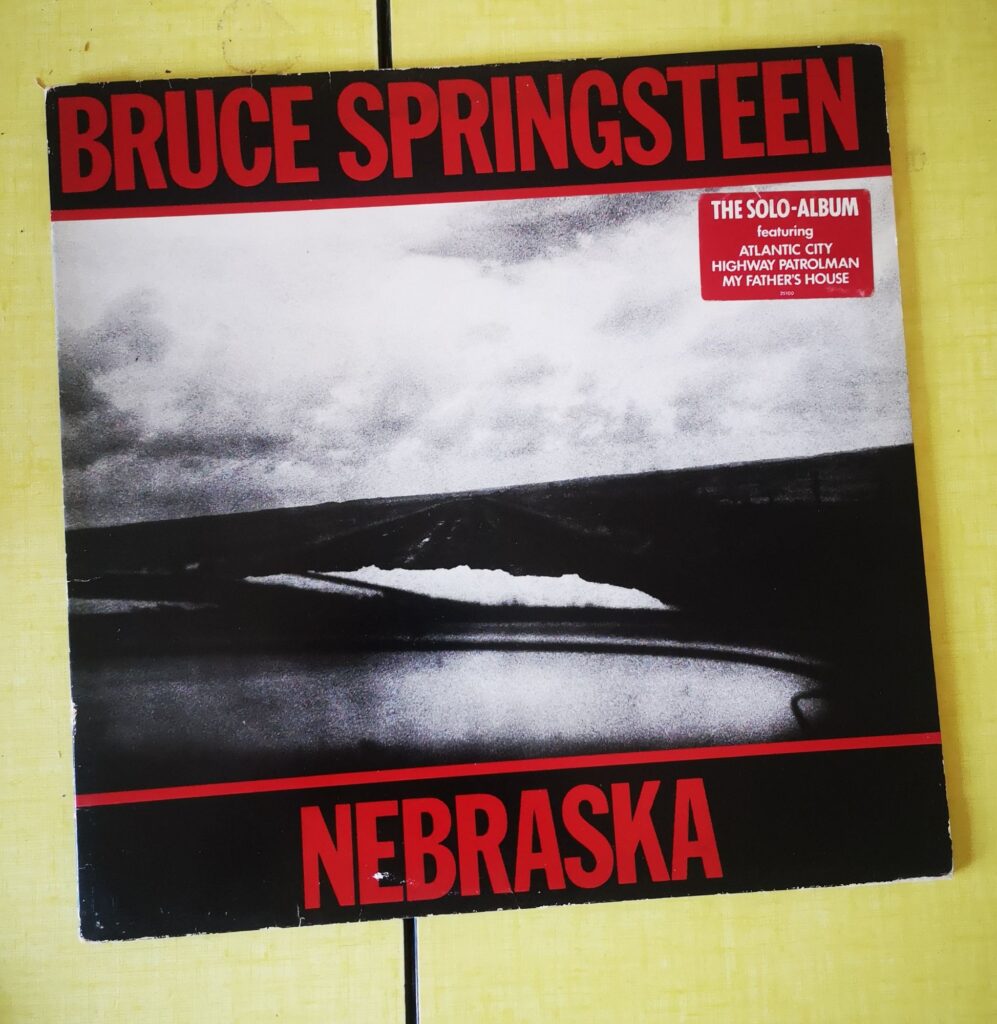

That album is Bruce Springsteen‘s Nebraska, orginally released in September 1982. It was a solo recording with voice, acoustic and electric guitars, mandolin, harmonica, and occasional glockenspiel overdubbed along with an extensive use of echo effect. While only moderately successful on release, Nebraska has since been recognised as turning-point moment in Springsteen‘s songwriting and performance.

An expanded version of the original album entitled Nebraska 82 plus a full-length movie called Deliver Me From Nowhere telling the story of how it was made are both announced to appear this week. It feels like the right time to take a look at why Nebraska is a collection of songs which I have been carrying around with me since 1982.

A Trail of Albums

Nebraska was Bruce Springsteen‘s sixth in a 9-year trail of albums and, although it would be eclipsed by Born in the USA which followed in 1984, Nebraska was a heartland which would take the artist quite some time to travel through. It has gradually earned a reputation as the archetype of an album made unknowingly by an artist1 who is invaded by the need to give space to a body of work which he himself does not fully understand at the time of its creation.

I had been on Springsteen‘s trail since 1973 and the day I saw an ad in Melody Maker for his very first record, Greetings from Asbury Park NJ. The ad said : “This man puts more thoughts, more ideas and more images into one song than most people put into an album.” I didn’t buy that record or hear it immediately. How could I have done that, living in the UK at the time? That would come with The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle, his second album, which came out a few months later which I heard, managed to buy and began to tell all my family and friends about.2 They would all unfailingly say : “Bruce … WHO!?”

I followed him patiently through the hype around Born to Run which brought him on tour to Europe for the first time in November 1975. I hitched my way to a historic concert at the Hammersmith Odeon London, which was sold-out and for which I had to buy a standing-room-only ticket on the street. The concert was impossbly good and I could hardly able to believe how well he played and sang.3

I waited and waited, keeping myself busy through the punk revolution, until June 1978 for the follow-up album which would be Darkness on the Edge of Town. I loved the quality of the writing, the intensity of the singing, and fire of the music. Then 2 years later came the prolific songwriting and international success of his fifth record, The River, a double album which convinced me that I would now no longer part of a cult.

The big question was : Where would the trail lead next?

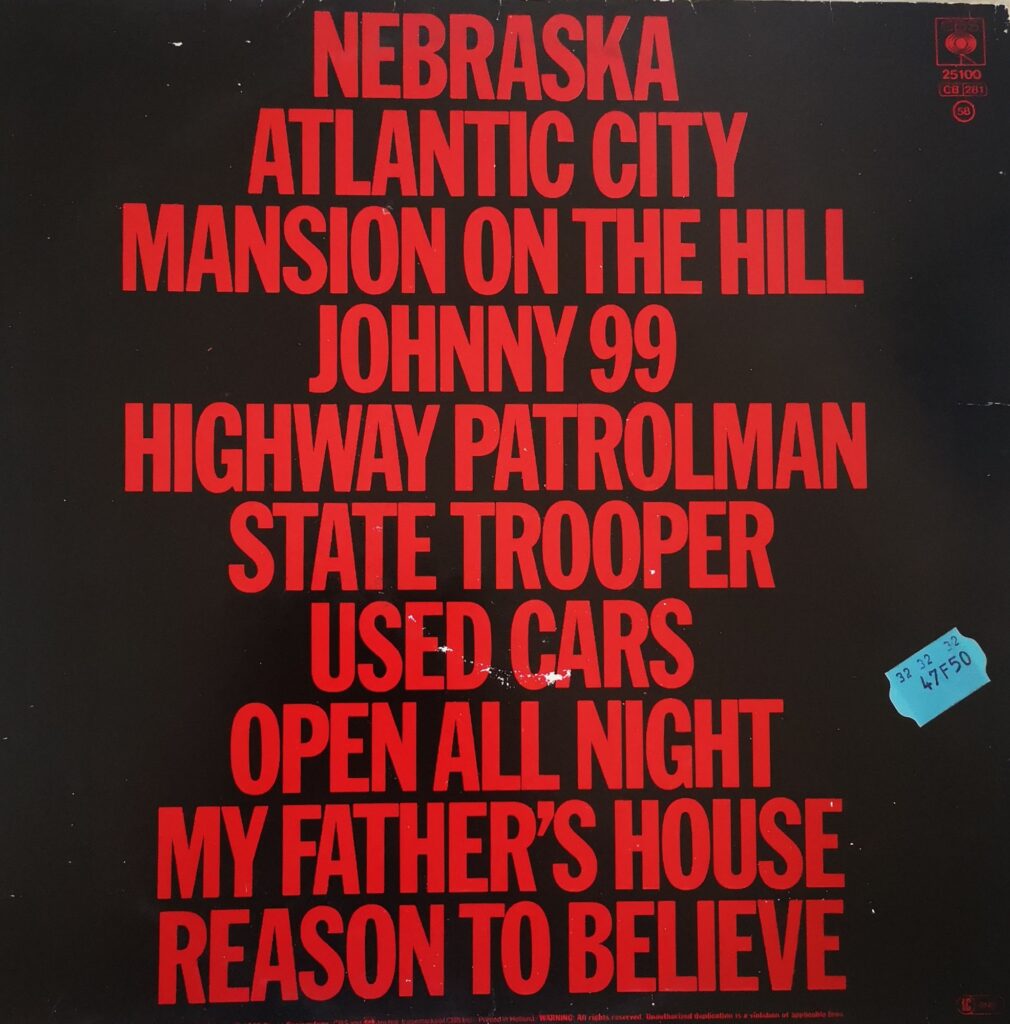

The answer would finally come one day as I was shopping at a supermarket in Toulouse France where I’d permananently settled by 1982 – in France, that is, not at the supermarket – when Nebraska was released. There it was. For sale. The front cover photo was odd, but the name was clear enough and the back cover had the titles of all 10 songs in big blood-red letters on a pitch-black background. I still have that copy with the original price tag on it.4

It definitely felt strange to be finding this record in a place that also sold food and household supplies.5 The record had a sticker which said it was The Solo Album – was that an invitation or a warning?

When we got it home, opening the gatefold cover, opposite a blurry photo of Springsteen we found the lyrics to the songs printed out in that same blood-red lettering on a pitch-black background which made your head spin if you tried to read it. On the snow-white inner sleeve which held the record itself, however, were French and German translations of the song lyrics in pitch-black letters.

As someone living in a country where English was still very much a foreign language for most people, I was impressed at the effort which had been made to help to give speakers of other languages access to the lyrics. English-language artists didn’t normally do that. The lyrics were actually easier to read in the translation than they were in the original – you just had to know the language. Somebody clearly wanted these songs to be understood. Or at least wanted to give people a chance to do so.

Each song carried a passenger

A man who put “thoughts, ideas and images” into his songs was one thing – with Nebraska came characters. Each song was definitely a story. This literary aspect took a while to sink in. Fortunately, the album was perfect for repeated listening. But we didn’t use the vinyl version for that.

At the time, my wife Sylvie and I used to carry a battery-operated mono cassette player in our car for music on long trips with our son Sam as we had no radio on board. We generally brought mix tapes with us in French and English, plus some classical stuff and jazz recorded off the radio at home. Even Indian music. Billie Holiday‘s early work was also a favourite of ours. So naturally we had a tape of the new Bruce album for the car. It was often a twilight choice.

As the day got darker, we’d slip Nebraska into the machine and watch the characters play out their stories on the windscreen of our trusty Chrysler Horizon as the road unravelled. With each song it seemed we were carrying an extra passenger who would briefly be there, tell their tale, then just as suddenly vanish at the end, leaving space for the next one.

Charles Starkweather told us the story of his ride through the Badlands6 of Wyoming with Nebraska, the opening song. Almost no melody, the voice ghost-like, with a story which began with a majorette and ended with a death in the electric chair.7

Atlantic City came next. It was a casino town story about what it’s like to be on the losing end of a winner-takes-all world. Musically brighter than the previous track, the story darkened as the narrator confessed he lost his job and had debts that no honest man could pay and only went to the casino to try his luck with the little money he had left – and lost that too. As he announced his first contract for the local underworld, he reminded us grimly that down here it’s just winners and losers and don’t get caught on the wrong side of that line.

Another passenger was an ex-auto worker called Ralph, aka Johnny 99, whose story began with a wolf howl. He was arrested for shooting a man dead. Turned out he also had debts no honest man could pay. But that wasn’t all : The bank were holding my mortgage and taking my house away. He finally told the judge that, rather than the 99-year prison sentence he’d been given for the shooting, he’d prefer the death penalty, please.

The wrong side of that line is a frequent feature in these songs. As we drove on, we also gave a lift to Joe Roberts, a Highway Patrolman who shared the dilemma he faced when bringing the force of law to bear on a member of his own family. Maybe his crazy brother Frankie just ain’t no good, but when it’s your brother sometimes you look the other way. What could the patrolman do when it came to one incident too many? Arresting Frankie was the only option but he admitted that he chased his brother through the Michigan back-roads, then let him slip away across the Canadian border.

The following song, the brooding State Trooper, was brought to us by a loner defiantly driving a car through the New Jersey turnpike with no licence or registration. We would listen to him pray that no officer would flag him down. Mr State Trooper please don’t you stop me, please don’t you stop me. What was he hiding? His answer was cryptic : I’ve got a clear conscience about the things that I’ve done. His life felt like one long night through which he had to keep moving to reach the woman he loved.

Bruce Springsteen himself paid us a first-person call as he wove images from his own childhood : in one, he looked up at a Mansion on the Hill, wide-eyed, listening to its sounds; in another, Used Cars, he described the disjointed feeling he had when watching the neighbours come from near and far as we pulled up in our brand new used car, swearing that the day the lottery I win, I ain’t ever gonna ride in no used car again.8

One cassette led to another

There were only so many minutes on each side of that home-copied cassette, which meant the tape would finish with Open All Night, an upbeat Chuck Berry style car song, and great to drive to. It is on Side 2 of the album but is not the last song. There was no auto-reverse on the tape, and it stopped there. The remaining spooky dream of My Father’s House and the hopefulness against all odds of Reason To Believe were on the other side. Did we want to flip the tape to hear the remaining two tracks? The very intrusion of that question interrupted the mood which is so important to the experience of listening to this album. Often it seemed impossible to go to those last two songs. Not because we didn’t like them, but because we would have to break the mood in order to get to them.

What I only found out recently was that Nebraska itself had long been an audio cassette carried as a passenger in Bruce‘s pocket – a single recording with no copy made, wrapped in protective lint because a standard case would have made it too bulky to fit in his jeans.

In his book about the making of Nebraska called Deliver Me From Nowhere, published in 2023, author Warren Zanes retraces the remarkable story of that cassette which Springsteen carried around for months playing it to people he trusted because he didn’t know what to do with it. In his 2016 autobiography the singer explains the songs were written quickly9, and each song took three, maybe four takes to record. The man who had spent endless hours of studio time trying to get a perfect version of Born To Run in 1974, had changed technologies completely this time, using minimal instrumentation and a four-track Japanese Tascam 144 cassette recorder.

After months of failed attempts to record better, more developed versions of these performances – only Born in the USA, Downbound Train, and Working on the Highway would appear 2 years later on the album Born in the USA played by the full E Street Band, and Pink Cadillac would appear as the B-side of a hit single – ten of the remaining songs would finally make it directly from that home-made cassette to the album Nebraska which I would ultimately come across almost by chance in a French supermarket amid the yoghurt and the washing powder.

A collection of dark bedtime stories

A word about the narrative qualities of this project. It was where Springsteen began to explore in greater depth the possibility of giving voices to different characters in his songs. As a reader, he had become interested in the short stories by Flannery O’Connor and realised that his own work was overblown, overwritten, and that he needed to hone things down. Looking deeper into the world’s meanness10, Springsteen came up with a new meaningfulness and what would be for him a radical new style of songwriting. He was no longer singing about his characters ; his singing was them speaking :

I wanted black bedtime stories. I thought of the records of John Lee Hooker and Robert Johnson, music that sounded good with the lights out. I wanted the listener to hear my characters think, to feel their thoughts, their choices.11

John Lee Hooker and Robert Johnson were black blues singers, of course. But when he talks about creating bedtime stories that are black he is also thinking of something dark, something sinister.

Chilhood bedtime stories are special. They help that transition from waking to sleep, from the ordinary world you sometimes wish you could forget to the world of dreams which you may or may not remember, because they offer narrative which can help to process the troubles of the day while soothing the worries of what might emerge from the shadows in the night. Wherever they come from, these narratives bring children and parents closer, developing language and imagination in the process.

In creating the dark bedtime stories of the Nebraska cycle, Springsteen tapped into a tradition of apparently gentle narrative but always with something scary or unsettling to share with the listener. To explain this mix of grimness and glockenspiel, the singer has often evoked the atmosphere of Charles Laughton‘s classic movie The Night of the Hunter where Robert Mitchum plays a preacher who terrifies the life out of two children. Springsteen explains that these new songs “began as an unknowing meditation on my childhood and its mysteries… I was after a feeling, a tone that felt like the world I’d known and still carried inside me.“12

Nebraska would turn out to be Bruce Springsteen on a search for something new artistically in which he would also come face to face with his own personal traumas. Here the artist who had given everything to be accepted by an audience would also unwittingly begin a new journey into psychoanalysis in which he would slowly begin to accept himself. But that’s another story. One of the many still to be told about this unfathomable album.

Sign up for the monthly newsletter on new posts

More Nebraska coming

You will find a YouTube playlist with the complete original Nebraska album here.

Meanwhile, keep eyes and ears open for those two important events coming this week putting the Nebraska recording in the spotlight. How will this sudden intense visbility suit such unusual material which has spent so long in the shadows ? Your guess is as good as mine.

Footnotes

- I first met this idea of Nebraska being unknowingly recorded by Springsteen in the pages of Deliver Me From Nowhere by Warren Zanes, 2016. The book is mentioned specifically later in this post. ↩︎

- The story of that discovery is told in Taking Brother Bruce Springsteen Home. ↩︎

- Here’s the setlist from the show. ↩︎

- 47.50 francs in 1982. According to the INSEE official government website francs-euros converter this sum would be equivalent to18.68 euros today. A new vinyl now costs almost double that price. ↩︎

- This easy access to a new Springsteen album takes me back to the day I tried to convince a record-dealer to accept an order for his second album. Here’s the gist of our discussion. It is November 1973 and, on my way home from school, I stop at the record department at the back of the Harlow, Essex Branch of WH Smiths and talk to the salesperson. I want to order a record, please. Are you sure we don’t already have on display ? I’m pretty sure you don’t. It’s called The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle by Bruce Springsteen. You could be right, young man, we might not have that currently on display. So you want to order ? I do. Now from the title and the artist – you are sure of those ? I’m certain. Fine, then we will have to wait until we get the new edition of our order catalogue next month to get the references and place the order. If I had the information now, would it be possible to order it today ? You would need all the details – artist, full title, label and catalogue number. I have all those. Great. You’re sure of the spelling ? I am. Yes, it was a long title, wasn’t it? And yes, it was Springsteen and not Springstein. Should take about ten days. It felt like passing an exam, but ten days later I got the record ↩︎

- Terrence Malick’s Badlands seen on late-night TV was Springsteen‘s source for the song Nebraska. ↩︎

- In 1985, Springsteen told his own version of the story behind the song – here is the video. ↩︎

- That echoed a childhood memory which still comes to mind about a vehicle of change in my own family. ↩︎

- Quoted from his autobiography, Born to Run, p 298. ↩︎

- A term employed by Starkweather to explain his acts quoted in Nebraska : “Sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” ↩︎

- Quoted from his autobiography, Born to Run, p 299. ↩︎

- Quoted from Born to Run, p. 298. ↩︎

One Comment

Pingback: